While digging through our archives, we found these notes from Dudley Hume, likely sent to Tom Turner back in the 90’s. There’s some very interesting insights, we hope you enjoy!

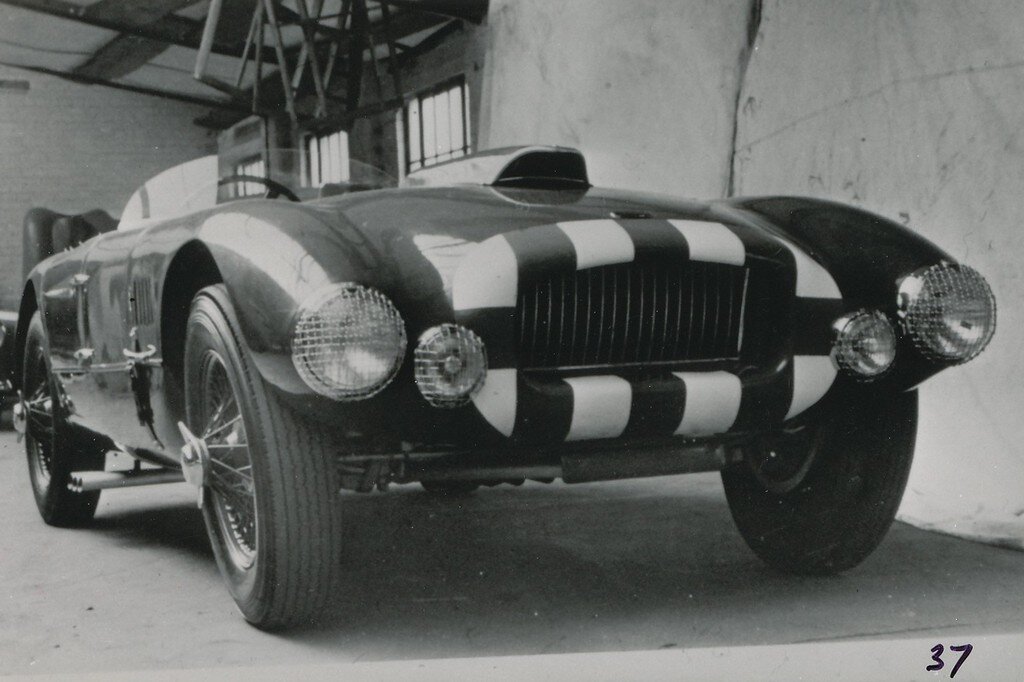

I was not directly concerned with body parts unless Reg Canham, Sydney's Production Manager, wanted a second opinion on a part he wanted the body builders to use, and they weren't being cooperative (as usual). Sometimes I would do a local layout to check that use of the part was feasible. I got a bit more involved in this aspect after I had redesigned the front of the Palm Beach, but mainly it was a matter of what our purchasing people (Eddie McDowell, Sydney's brother-in-law) could obtain at the right price. Concerning fenders, wings or mudguards for the K1, M1 and also the L and P1, these were intended to be the same within the normal variations of hand-made parts. Although there were two sources manufacturing our body parts, Hiltons and an outside supplier, Messrs. Ball and Friend. I remember hearing discussions on the fit of the outside supplier's wings on several occasions. I have to admit that I thought the K2 wing was the same as the K1, but they are quite different. In addition to the air intake slot, their wing is several inches longer and fits differently to the body.

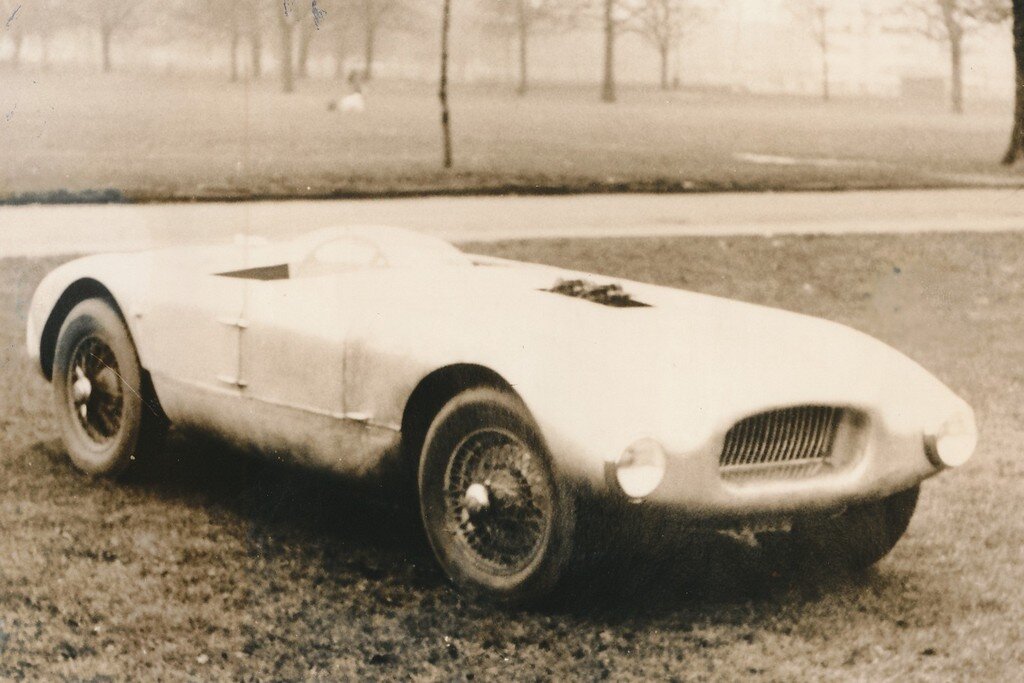

Concerning the sale of unfinished vehicles, the following might be of interest. Untrimmed vehicles simply had no seats, hood, carpet or side panels and sometimes the wooden fascia surrounding the instrument panel was also missing. Unfinished vehicles sometimes had the rear section of the body missing so that the customer's coach builder would either put on one of their own design or fit the Allard one later. See note on tax situations. These vehicles were sometimes not wired up, and the trim was usually missing; either it would be carried out locally or to fit Allard parts later. Skeleton chassis meant that no body at all except the bulkhead, fire wall, and sometimes no engine or gearbox.

All these offerings were intended to save the customer excessive tax. At that time, we had a tax happy socialist government who instituted a 25% tax on cars costing less than a thousand pounds, but this was doubled if the cost was over one thousand. Of course, the main objective was to persuade manufacturers to export as many cars as possible to earn dollars. This tax made our cars expensive in complete form on the home market, so to overcome this we sold unfinished vehicles to the customers initially for tax purposes, and then we sold the remainder of the necessary parts either to the customer or to his coach builder at a later date as required. They didn't always take our trim or parts, of course, especially if the coach builder was offering to do the job at a lower price.

Your query concerning the lack of a stop light caused me a chuckle. At that time, there were very few legal requirements in the U.K. for private cars, and stop lights were not one of these. However, the electrical manufacturers did provide the necessary parts for stop lights and most vehicle manufacturers did fit them. Allard did, of course, but if the car was to be finished off by a local coach builder, they wouldn't necessarily fit a stop light. Obviously, coach builders all over the country were engaged in these "finishing jobs", but quite a number were sent to Abbots of Farnham Surrey. They also did work for Aston Martin, Ford, and Vauxhall (special estate cars) and convertibles on Rolls and Bentley.

Of course, this business of buying the vehicle piecemeal was strictly speaking illegal, but when the regulations were drawn up, they didn't allow for this sort of "ingenuity" on the part of small manufacturers and customers who were eager for "different cars" to the run of the mill, mass produced items.

Concerning Ford parts used on Allards, firstly, all standard "Allards" including some J models were fitted with the 3.6 liter 21 stud Ford Pilot engines, which were the only large Ford engines available at the time until the 2.2 liter Zephyr engine became available in 1950 and for which we designed the Palm Beach.

During WWII, Allards (Adlards, the Ford main dealer) were concerned with carrying out complete servicing of Bren carriers (a small tracked vehicle for carrying up to six soldiers and with a Bren gun mounted up front). These vehicles were fitted with a Canadian Ford Mercury 24 stud 3.9-liter V8 engine. When the war ended, quite a number of these units were "in stock" at Adlards, mostly new but some reconditioned. Sydney needed a more powerful unit for the 12 and so the Mercury units were brought into service, bored out to 4.2liter and then up to the maximum possible 4.4 liter.

I can't tell you anything about the financial arrangements over the engines between Allard and the government.

The aluminum cylinder heads and twin carburetor manifolds were of our own manufacture, similar to Edelbrock, for both 21 and 24 stud engines and were made by Birmingham Aluminum Company. We had a lot of trouble with the porosity of the castings, and we designed a test machine to test every head before full machining.

So far as the use of other Ford parts were concerned, when Sydney started making cars after the war, he purchased the Ford Pilot front axle beam, stub axles, hubs, ball joints, and track rods; but the beams were cut in half and bosses welded on for the rubber bushings to form the divided axle suspension. Because of the additional leverage loading caused by the divided axle geometry, the Pilot front spring could not be used so a special one for Allards was produced by Jonus Woodhead of Leeds in Yorkshire.

Apart from the 3.6-liter Pilot engine, he took the standard Ford clutch, the three-speed gearbox, the Pilot torque tube and drive shaft cut down to suit the Allard. The engine was mounted much further back than in the Pilot. Pilot rear axles were cut down to reduce the track for the early Land K models. The radius arms which stabilized the torque tube and axle assembly were also cut down to suit (This was the oval tube material used for front shock absorber (or damper) anchorages on the chassis). All this cut down work was carried out by a real nut of a character with a small blacksmith's shop in Balham, back street about 3 miles away from Park Hill. He was a Polish fellow named Scatula (we called him Scat.) His English was difficult to understand, but he could take on any heavy metal job and was remarkably quick. I don't know what Allards would have done without him in the early days.

Before I joined the company, nothing was actually designed; it was mocked up full size and fixtures made from the finished shape or pattern. Very little was put on paper for record purposes, and when I joined, I found there was no service information available and no one appeared to be interested except Reg Canham. In no time at all, anybody with a service problem or query, mostly dealers and garages, were put onto me. I soon realized I would have to rectify the situation or be overtaken by it. I suspect Reg Canham was relying on this.

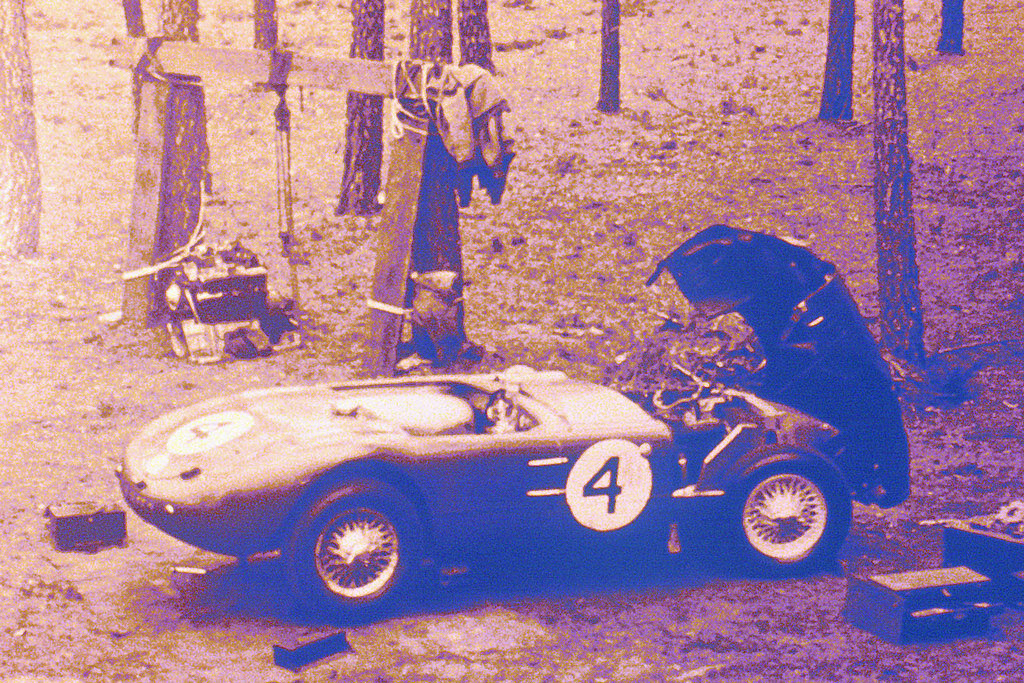

So having overcome one or two of the most pressing production problems by producing drawings to guide the workshops, I set to and produced about 20 service illustrations of the most prevalent service problems in about two weeks, including weekends and issued copies of all of them to the Ford main dealers and garages who were handling Allards. The constant phone calls died out and I was able to concentrate on the much more interesting business of engineering the troublesome items to eliminate the queries for good. Having overcome the service problems "more or less", I then set out to get everything down on paper (many parts had never been drawn out) and to reduce costs by improving methods of manufacture and improve reliability. Some of the bracketry was inclined to fracture after awhile. Particularly fan brackets and wing supports. Probably more on M's and P's.

Initially I only had two lads working for me, but this went up fairly soon and eventually I had eight people in the drawing office. Usually two or three of these were apprentices as part of their training. One who was really worth his salt was Dave Hooper, who joined me in the office just after I designed the P2 and K3 chassis and was just commencing the design of the Palm Beach Mark 1 chassis. I first met Dave when we were making jigs for the P2 chassis. Jim Saunders, the shop foreman, a delightful fellow with a deep country burr, who was related by marriage to Sydney, recommended Dave to me as a lad who would be of some real help in the office. He was right. Dave was outstanding.

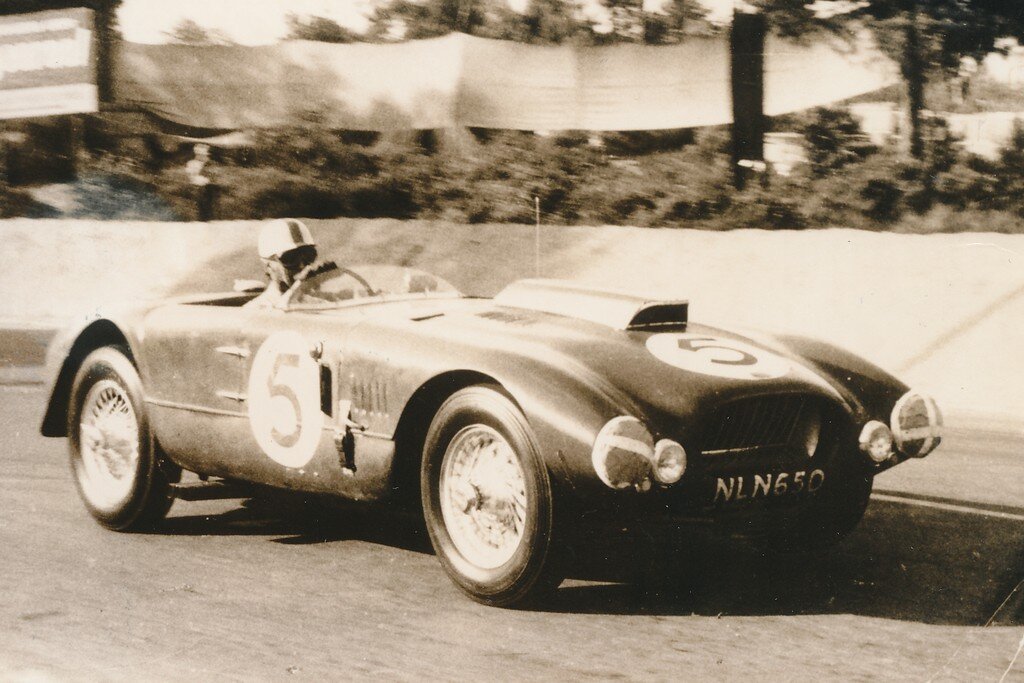

Of course, everything I designed was drawn out first as it should be before it was made, and from the P2 onward we tested the chassis regularly. We took them to the MIRA Proving Ground in Warwickshire and tried to break them on the corrugations and pav'e. The P2 stood up without failure and this was regarded as okay since it weighed 100 pounds less than theP1 chassis and was torsionally five times as stiff. We did have one problem, though. The chassis was being driven on the "rough country" track one day when a stone severed a brake pipe on the rear inboard brakes. To get us back to Clapham, we pinched the pipe closed and I drove on front brakes only with Zora Duntov in a J2X "riding shotgun" to give me a bit of braking distance. Every now and again I would lock up the front wheels and the resulting squeal caused Zora to look round quickly in apprehension. Naturally we repositioned the pipes to ensure that that didn't happen again.

Zora Duntov often came with us to the MIRA Proving Ground to check on J2 and J2X performance with either the 5.4-liter Cadillac or the Ardun conversion on the Mercury. He also did work on the mechanical and wind losses.

So far as the use of Ford parts were concerned, the policy was to use them wherever possible for wear and tear items such as kingpins, bushings, etc., ball joints, wheel bearings, engine, clutch, transmission, rear axle, but otherwise we used our own or proprietary items to give an overall impression of individuality and not of a Ford special.

From the very first post-war cars (L Tourers), the brake system was Lockheed throughout to suit Allard, (modified Humber super snipe). We did not use the Pilot system which was a curious mix of fluid front and mechanical rear, and drums were smaller. As you know, the Allard always used the proprietary MarIes steering box rather than the Pilot box. I personally have been of the opinion since those days that the MarIes box was not man enough for large Allards; we should have used the Burman re-circulating ball box, as Jaguar did. Having driven that Safari at Monterey, I am quite convinced. The Ford Transit box would be quite suitable, but it would mean refabricating the chassis mounting.

The steering wheel was a Bluemel proprietary item used on most British sports cars at that time. Instruments were always Smith, Lucas or Jaeger. Wiring looms were designed and made for us by Lucas (except when we couldn't afford to pay them and we made our own). From about 1948 onward, front suspension axle beams were Allard forgings; also stub axles and steering arms, but of course machined to suit the Ford kingpin's bearings, etc. As all the large Allards, L, K, M, P and 12 had the common 4 ft 8 ½ inch front track, the basic assembly was the same except for the caster angle set in the beams. When the progressive changeover to coil springs came, the same beams simply had the spring pans welded on.

When I introduced the X suspension, we went away from the Ford radius rods to our own forward-facing tubular items with proprietary rubber bushings, but still used the Ford patterned fork to the axle beam.

For the Palm Beach Mark I with a track of 4 ft. 4 in., we simply had a shorter forging of the axle beams made and shorter tubular radius arms. These items were also used on the JR, but for the Mark II Palm Beach, I designed a McPherson system. The American marketing people insisted on it - wise fellows. This system had no Ford parts in it. They were all unique. Due to the low wing line, it was not possible to use the Ford McPherson strut.

Of course, springs were always designed to suit the weight of a particular model and the dampers were calibrated to suit. These were usually either Woodhead Monroe or Armstrong.

Ford parts for our vehicles came directly from Ford to gain the price advantage allowed for original equipment. Also we had to take the complete assemblies, i.e. complete front axle, complete engine, gearbox assembly, complete rear axle/torque tube/radius rod assembly. We then had to strip down to modify to our specs and return the brake assemblies, etc., for credit. (Scatula did this work.)

I mentioned earlier I was not directly concerned with body fitting unless Reg Canham wanted the body builders to use a different item for whatever reason, and they were resisting the idea (they usually did). Reg would either ask for my opinion or ask me to do a local layout to ensure that the idea was feasible. We always used standard proprietary units, usually from the Wilmont Breeden catalogue. This was necessary to get the much lower first equipment price. Unfortunately, if we owed them a lot of money and they were baulking, we would have to purchase from a local distributor at a much higher price. The quarter window units used on the MI and the PI were a proprietary item but I don't think they were Wilmont Breeden. I believe they came from a windscreen specialist whose name I cannot remember but it may come to me.

The matter of the numbers of components ordered had to depend, as you may have gathered, on the state of our coffers and how much we owed to other suppliers. Obviously, there was usually a price advantage in purchasing a large number, if we could afford it. I don't think we ever purchased as many as 50 quarter windows at one time. It was more likely to be 20.

Concerning the taillight/number plate housing assembly, there was no legal requirement to use any particular type, providing the number plate letters were of the standard size. But this type of assembly was regarded as up market.

I cannot offer any suggestions about your rear lights that showed mostly white to the rear, as this was one of the few legal requirements that was enforced, i.e. only a red light must show to the rear. The Department of Transport resisted the fitting of white reversing lights for a long time until manufacturers produced a fool-proof automatic switch system within the transmission.

Your comment concerning Ford parts from your local antique Ford supply house is explained by the fact that Ford U.S. did at that time, before and after WWII, determine all design and engineering in U.K. and it was based on earlier U. S. practice. The 22 h. p. Ford four door saloon from 1932 to 1939 was basically the same vehicle made after the war, with a larger engine and revised radiator grill and called the Pilot.

Allard, of course, took only large car Ford parts available at that time, but you will appreciate they were mostly of pre-war design and mostly first produced in 1932. During that period, Ford did not change designs or specifications very often. People who purchased cars in the U.K. at that time tended to be very conservative in their outlook and Ford played along. None of your Johnny Come Lately upstart redesigning things; whatever next, to improve the ride! what have horses got to do with it? At the time, that was a serious attitude, and, I'm afraid, for some years afterwards.

---

The use of sheet steel rather than aluminum for the inside panels on all models was partly because aluminum was on a very strict quota. But also, it was very expensive compared with the low-grade steel sheet used for "flat" panels. Another problem with the aluminum panels used under wings, etc., and attached to steel in conditions of moisture and poor ventilation, is corrosion.

Concerning suppliers large and small, we were always in difficulties with this business of "economic" quantities. Our best average production rate was 15 cars per week and was not usually sustained for more than 3-4 weeks at a time. Sydney did not concern himself with day to day financial problems with suppliers. We had a lady company secretary, Mrs. Weeks, who was feared and respected by everybody and she did the day to day book balancing. Whenever an item or supplies got "critical", she would inform Eddie McDowell, who would then purchase elsewhere or at a reduced rate. I have often thought that if it had not been for Mrs. Weeks on the financial side and Reg Canham on the production side, the company would not have lasted a couple of years. Sydney knew what he was doing putting them in charge.

Reg Canham was General and Production Manager of Allard Cars and was also a Director from the beginning. He was hard working, keen, lively and very critical of people who weren't. He was always prepared to listen to suggestions from others, but he was very unpopular with a number of people on the Allard head office because he considered that they were overstaffed. Reg was concerned about this and frequently said so. This caused a lot of resentment, of course, and some people were always trying to put him down by describing him as a salesman. Well, he was before the war, but an awful lot of successful businessmen start off as salesmen. That sort of talk can do nothing to minimize Reg Canham's influence on the company. I strongly consider that Reg deserves a special mention as above.

Reverting to hardware, I am surprised that you were not able to find correct door handles but I think you are right about bonnet handles being all the same except the JR. I have to admit that I cannot remember the interior handles but I do remember that the outer handles for the P1 were large and different to the ones used on the M1. The aluminum stone guards on the rear fenders were used to protect the lower front faces of the rear wings from stones thrown up by the front tires. They were made in our shops and were not originally fitted as standard on earlier models until the customers complained of stone damage to the paint work. The paint was a lot softer in those days. Two patterns would fit all fenders (the same parts would fit J2, J2X, another pattern would fit L, M, K1's, and K2's).

Upholstery and trim - I'm afraid this was made in the shops as the cars came along. There were never any drawings, and only the trimmers kept patterns which they had made themselves. But these were approved by Sydney and Reg Canham.